Journal of Latin American Anthropology

Journal of Latin American Anthropology

Film Review

Thunder in Guyana, 2003. A film by Suzanne Wasserman. 50 min. Colour. Distributed by Women Make Movies, 462 Broadway, 5th Floor, New York, NY10013; phone (212)925-0606, e-mail cinema@wmm.com,http://www.wmm.com.

by Percy C. Hintzen, University of California, Berkeley

President Janet Jagan

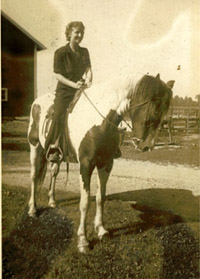

Janet Jagan on horseback

/ Young Janet - 1930s

/ Young Janet - 1930s

She was a world-class swimmer who took flying lessons and rode horses. She was the ideal American beauty. And she was an intellectual. She met Cheddi Jagan while enrolled as a student at Wayne State University in the early nineteen forties. Clearly, she was aware that the promise of America was not available to her, something that she was unwilling to accept. Her Jewishness, she believed, came with the perpetual condition of being the underdog. Rather than accept the limitations of Americansociety, she chose to leave and to create the conditions of her own dignity and the dignity of humanity elsewhere.

Janet Jagan speaking at podium - 1997

/speaking to workers 1940s

/speaking to workers 1940s

The sympathetic airing of Janet Jagan’s story by Wasserman, the daughter of a first cousin who was clearly enthralled with her life, is rooted in the personal and the familial. It has the quality of a journey of redemption for a family who rejected most of what Janet Jagan did and stood for. And there was much to reject. She openly challenged the capitalist status quo in the 1940s. She dated and eventually married an equally radical Asian Indian from Guyana who was studying dentistry at Northwestern University. Their relationship was transgressive in every way. He was Hindu and he was foreign. Her father refused to meet him because, in his racially jaundiced eyes, he was “Black.” He threatened to “shoot him on sight.” Her grandmother had a stroke when they married.

Despite the sympathetic treatment of her great aunt, Suzanne Wasserman cannot escape the American lens through which her interpretation of Janet Jagan’s radicalism is filtered. She succumbs to the use of the “Marxist” and “Communist” labels in describing the ideology of the Jagans and the government that they formed in the fifties despite their own rejection of these labels. These were the very justifications used by the United States and Britain to oust them from power on two occasions, in 1953 and 1964, the latter in a campaign that Janet Jagan predicted, correctly, would lead to a future of endemic violence and turmoil for the country.

Wassermann’s concern with the familial and personal leaves gaps in her understanding of the relationship between Cheddi and Janet. They were extraordinary in their similarities, a point that can be missed when viewed through obscurantist racial, national, cultural and religious lenses. They were both extraordinarily attractive physically. Both were born into societies from which they were excluded on religious and cultural grounds. They both possessed profound and critical intellects. And both managed to overcome the strictures and limitations that their respective societies placed on them. One could sense the profound chemistry in their relationship and the reason for their singular pursuit of freedom and human dignity for everyone. They returned to the English colony of British Guiana soon after they met and married. Immediately, they mounted challenges to the colonial status quo by organising the most dispossessed: the sugarcane workers and she the domestic workers. This catapulted them to the leadership of the nationalist movement.

Their challenge was not merely to colonialism but to capitalism itself. In 1953 the People’s Progressive Party, which they founded won office in the first elections held under universal suffrage. Cheddi became the colony’s first Premier and Janet its first woman member of the cabinet. She also became the Deputy Speaker of the colony’s parliament. Quickly, the Jagans became lightening rods in the cold war anti-communist crusade by North America and Western Europe. And Janet Jagan, as the white American woman who had stepped out of line, became cast as the evil genius behind a gullible husband. The British ousted their Party from power in 1953. The Jagans were both imprisoned.

They survived, unbowed, to be elected to national office once again in 1957. Cheddi Jagan became Chief Minister with Janet holding the important cabinet post of Minister of Labour, Health, and Housing. They Party remained in office until 1964 during a period when the country saw its greatest achievement in education, agriculture, health, welfare, and economic development. But they could not survive the U.S. interventionism that intensified after the Bay of Pigs fiasco of 1961. The United States collaborated with Great Britain to change the constitution. Despite receiving the largest percentage of the vote, the Party suffered an electoral defeat orchestrated by the machinations of Great Britain (the documentary incorrectly states that the Party received a majority of the votes, which it did not). Janet and Cheddi Jagan had become poster children in the international campaign against communism. But the ire of the anti-communists was directed particularly at Janet. She was labelled as one of the most dangerous communists in the hemisphere and was compared to Eva Peron by the New York Times. Both Jagans got special attention from Winston Churchill and John F. Kennedy for whom they had become objects of derision. In the propaganda campaign Janet was identified, erroneously, as related to Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

Cheddi & Janet at home 1992

/Wedding photo - 1943

/Wedding photo - 1943

Cheated out of office, Janet and Cheddi continued their campaign for freedom and civil rights until, in 1992, their Party, the People’s Progressive Party, won the first free and fair elections held in the country since they were ousted in 1964. With Cheddi Jagan as President, they picked up from where they left off, turning the country’s economy around and restoring stability. When Cheddi Jagan died in office in March 1997, Janet was persuaded to run for the Presidency. She won and spent 20 months in office until a heart attack forced her resignation. In 2003 when the documentary was released, she was still working at the Party’s Headquarters. She was 83 years old.

Throughout her life, her family ties remained strong. She reconciled with her father who died during the period when she was restricted from travelling by the British. Tellingly, the only regret she uttered in the entire documentary was that her father and husband never met. Today, Janet Jagan is no longer an anachronism. While in office, the relationship between the government she headed and the United States was friendly and cooperative. And while she was reluctant to label herself, her daughter in law, Nadia, made the observation that she was “more Guyanese than most.” Perhaps she has become the epitome of what all Guyanese should be. And certainly a beacon of hope for the United States. She is a woman who not afraid to think the unthinkable.