Book Reviews of Books Written about The Jagan's

Cheddi Jagan and the Politics of Power

By Perry Mars

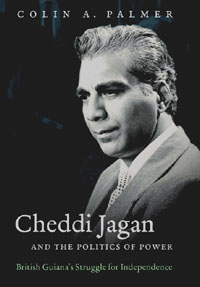

COLIN A. PALMER. Cheddi Jagan and the Politics of Power:British Guiana’s Struggle for Independence. (H. Eugene and Lillian Youngs Lehman Series.) Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. 2010. Pp. 363. $39.95.Colin Palmer’s book on Cheddi Jagan is the latest addition to the many studies that seek to elucidate the role of colonialism and the Cold War in frustrating the democratic aspirations of the Guyanese people. Preceding this remarkable, well written, and skillfully organized work are other capable contributions from scholars like Raymond Thomas Smith, Leo A. Despres, Stephen Rabe, Maurice St. Pierre, and Cheddi Jagan himself. So what new insights on Jagan or Guyana can Palmer deliver in this, the most recent of his works on Caribbean political leaders?

For this book, Palmer utilized extensive and copious documentary research from among some of the richest of colonial and U.S. archives. His main thesis seems to be that Guyana’s past and current dilemmas, such as delayed independence, ethnic divisiveness, and recurrent political violence, derive from the weaknesses and failures of the Guyanese political leadership in general, and that of Jagan and his People’s Progressive Party(PPP) in particular. Palmer characterizes the so-called weaknesses of Jagan and the PPP in terms of their supposed “naivety” or “irresponsibility” in clinging to a self-defeating communist or Marxist dogma within British and American spheres of influence and control. Yet, the British knew that the realization of Soviet or Cuban communism in Guyana was highly improbable, and that Jagan’s policies were basically nationalist and pragmatic.

Jagan was castigated for his role in initiating and fomenting racial politics and violence. Historical evidence, however, shows that the racial and ethnic divisions that followed the party split in 1955, and ignited political violence between 1962 and 1964, were mainly instigated by British and American governments in order to prevent the supposedly communist Jagan from obtaining political power. Jagan’s national political opponents, Forbes Burnham and Peter D’Aguiar, were more directly culpable in this racial and political conspiracy, given their collusion with colonial and American authorities. Admittedly, Jagan eventually resorted to the political expediency of ethnic mobilization, which has characterized the entire Guyana political landscape since the early 1960s.

Palmer displays obvious sympathy for Jagan’s struggle against British and American Machiavellianism. Yet he tends to downplay Jagan’s leadership and ability to navigate a process so overwhelmingly stacked against him. This dismissal of Jagan’s strengths no doubt saves Palmer’s main thesis, which emphasizes leadership weaknesses in Guyana’s nationalist movements at the time. Similarly, no effort is made to counter the unsubstantiated and seemingly racist insistence of the colonial and American officials that the only real intelligent and capable leadership in the PPP was provided by the white, U.S.-born Mrs. Jagan, despite much historical evidence to the contrary.

Historically, Jagan’s leadership capabilities are shown by his resilience against foreign and domestic forces and his eventual triumph in regaining the presidency and international respectability in 1992. Also, Palmer’s main conclusions—hat the 1954 Robertson Commission inspired and instigated the 1955 PPP split, that the Colonial Office exaggerated the communist bogey to deny independence for Guyana under Jagan, and that Jagan and the PPP, between 1953 and 1964, were merely in office but not in real power—have been identified and exposed by Jagan since the 1950s. Jagan was also a visionary as the earliest and most consistent advocate of coalition politics embracing Guyana’s Africans and East Indians as a necessary means towards political stability and development in the country.

Palmer’s historiography is conventional and relies heavily on Colonial Office and U.S. State Department documents. He paid little attention to Jagan’s many writings and speeches, as well as other domestic sources, including the PPP’s periodicals. This more grounded approach is necessary to counterbalance the biased assessments of British colonial and U.S. officials and pro-British newspapers in Guyana, which the author tends to privilege. Nevertheless, aside from these omissions, Palmer’s book makes interesting reading and is particularly valuable for advancing, so far, the clearest and most persuasive statements about the critical connections between foreign conspiracies and interventions and Guyana’s traumatic struggles toward democracy and political independence.

PERRY MARS -Wayne State University -Printed in AMERICAN HISTORICAL REVIEW DECEMBER 2011

Review by Ralph Ramkarran

Cheddi Jagan and the Politics of Power

Colin Palmer’s Cheddi Jagan and the Politics of Power – British Guiana’s Struggle for Independence, published a few weeks ago, is “an examination of the ways in which the colonial regime joined hands with the United States and local elites to destroy a political leader whom they distrusted and feared.” Colin Palmer is Dodge Professor of History at Princeton University. His history begins in 1953 and ends in 1964 with an Epilogue encapsulating subsequent events.

Academic interest in Guyana’s modern political history has grown since the release by the C.I.A. of its records a few years ago. Professor Stephen Rabe’s “US Intervention in British Guiana – A Cold War Story,” published in 2005, was the first study after the release of the CIA’s records; Colin Palmer’s book is the second in what is likely to be continuing interest in the history of Guyana and an enduring fascination with Cheddi Jagan, whose international stature in colonial political history grows with each passing day.

Interest is generated by the story itself – an impoverished colony, a small population, of no strategic value, a dazzling group of radical young men and women, with a charismatic leader, boldly challenging British authority, twice removed from office by imperialist intervention, are some of the elements which come together in the compelling drama of British Guiana between 1953 and 1964.

Much of the story is already known but Palmer adds new information, and redefines what is already known, adding tantalizing new questions. Palmer convincingly demonstrates that the policies and postures adopted by the P.P.P. in 1953 was reformist in character and scope, “tone and emphasis,” although “stridently nationalist…..the notion that the Guianese leaders were Russian puppets was profoundly misguided and constituted a gross misunderstanding of their nationalist aspirations.” It is doubtful that the press, mainly the Argosy, but the Graphic as well, was misguided.” Reflecting the fears of the ruling colonial elite and their “local enablers,” it created the hysteria of “communism.” It reflected the unexpected and traumatic impact on them of the election results which it attributed to the docile and illiterate masses being duped by communists. To borrow a phrase from elsewhere in the book used in a related context, the PPP’s victory produced in the colonial elite “fits of political apoplexy.”

Governor Sir Alfred Savage did not initially buy into the narrative and was prepared to work with the PPP leaders. But something happened along the way. It could be that the continuing “stridency” of PPP leaders or their attendance at conferences of “communist” affiliated organizations, the unrelenting anti-PPP press, continuous pressure from the elites, all nudged him towards a change of opinion. But a strike in the sugar industry may have been the catalyst. In the end his dispatches seemed to have played a major role in influencing the colonial office to intervene. The American Consul General criticised the suspension of the constitution and blamed Savage for the misjudgment.

The Sugar Producers Association, with which Ashton Chase was negotiating, on whose behalf is not quite clear, offered to recognize the Guyana Industrial Workers Union for field workers and the Man Power Citizens Association for factory workers. This was rejected. On hindsight, it is tempting to speculate what the political outcome would have been if the compromise had been accepted having regard to the crucial role that Bookers and Jock Campbell played in encouraging the British Government to suspend the Guiana Constitution with the use of bayonets.

British Guiana was the victim of two coups. Palmer described the suspension of the constitution as one coup, and as “constitutional terrorism.” The hijacking by Burnham and his supporters of the 1955 special congress of the PPP in 1955, resulting in the split of the Party into two factions, and eventually the PPP and the PNC, was described as “the second coup d’etat that British Guiana had experienced in the commanding heights of its political system in two years.”

Palmer quoted a Foreign office document for evidence of British involvement in the split. “The split in the PPP undoubtedly owed much to the patient work by the Special Branch who deserve the highest praise for this achievement.” It explains that the governor “has at his disposal an efficient Police Special Branch under confident and experienced leadership.” Palmer concludes that “this is an astounding admission of British complicity in the acrimonious divisions in the ranks of the PPP.” He explains that the nature of the interference is not known and suggests that “it may have taken the form of financial inducements to dissident PPP members to participate in the coup.”

The hapless Governor, Sir Alfred Savage, did not survive. He was recalled in June, 1955, having lost the confidence of local elites, the colonial office and, more importantly Jock Campbell of Bookers, for failing to destroy the PPP. Janet Jagan, Campbell declared, is “a proved communist” and should be deported, “possibly to a Soviet country.”

The failure of the British to destroy the PPP, despite its sustained assault, was due to the popularity of the Jagans and the PPP. “The party identified with the needs of the people, thereby earning their support and loyalty, but never lost sight of its larger objectives: self-government and political independence.” While elitist politicians worried about the estate providing meals and sleeping accommodation when they went into the sugar estates to campaign, Jagan “together with his wife, had spent years going into these same areas eating, sleeping, and talking with the people, and it was this that had won him the affection of the people.” He said that they possessed that “rare but indefinable quality to obtain and sustain the abiding trust of the people in whose name they spoke……The Jagans had kept faith with their admirers, a quality that meant the efforts by the colonial regime to discredit them failed because the wellspring of their support was deep and suffused by a passionate, religiouslike fervor.”

Part 2

In the first part of my review of Colin Palmer’s Cheddi Jagan and the Politics of Power – British Guiana’s Struggle for Independence, which was recently published, I dealt with his analysis of the period of 1953, the suspension of the constitution and the effort of the British Government to destroy the PPP as a political party and Cheddi Jagan as a political leader.These efforts were not successful. The Robertson Commission recommended a period of “marking time…..to create a healthy political environment.” “It was guided by the obsession to contain or destroy the PPP,” argues Palmer. During its hearings it displayed a dismissive and patronizing attitude to Guianese, which was deeply embedded in the consciousness of the entire colonial apparatus, including the Governors, whose private comments on Government Ministers, including Jagan, were unfailingly paternalistic. The interim government installed as a result of the recommendations of the Robertson Commission, represented the interests of the colonial elite and lacked credibility.

It soon became apparent that the period of “marking time” was unsustainable and having engineered the split in the PPP, the British Government restored elections in 1957 at the urging of Sir Patrick Renison, the newly installed Governor. The PPP won the 1957, as it did the 1961 elections, the latter under an advanced self-governing constitution with a promise of independence under the party which won those elections.

While Palmer recognizes the deep and passionate commitment of Cheddi Jagan to the poor and exploited, he falls prey to some of the propaganda which was unleashed by the same opponents of the PPP that he scornfully exposes, leading to contradictory conclusions. He judges that the PPP pandered to racial sentiments citing Jagan’s attitude to the West Indies Federation as evidence. Referring to the fears of Indians mentioned by Jagan in his 1954 speech to the PPP congress when dealing with the W.I. Federation, Palmer does not refer to the more fundamental position articulated many times by Jagan and mentioned in his “West On Trial” that the W. I. Federation was a colonial imposition, the object of which was to maintain and extend political domination and economic exploitation and predicted that it would fail. And it did. Like all other federations established by the British, the W.I. Federation failed, the immediate reason being a structural imbalance – a weak centre and strong units. The same problem faces Caricom. Nevertheless Palmer sympathetically quotes George Lamming’s view that on the Federation issue Jagan was forced to tread delicately and never wanted a party that was not ethnically all embracing.

He uncritically repeats the colonial view that Jagan was a poor administrator but ignores Jagan’s establishment of the Riumveldt industrial Site, the beginning of the MMA/ADA scheme, Tapacuma, Black Bush Polder, the expansion of electricity, education, health services, housing in the city and sugar estates virtually abolishing the logie, rice and sugar production. These defined Jagan not only as a visionary in economic planning but also administratively capable of delivering on some of these plans as well.

However, notwithstanding these and other negative assessments, his overall conclusion about Jagan was positive. “……he could be also ideologically elastic, simultaneously embracing and articulating political positions that had a variety of roots. These existed in dynamic tension and constituted what can be properly called ‘Jaganism’……but beneath all the rhetorical fulminations, vacillations, and incoherence, Cheddi Jagan’s consuming commitment to the welfare of British Guiana was never in doubt and shone through with admirable consistency and passion.” Palmer praised the depth and quality of Jagan’s writing, particularly its analysis of Guiana’s problems. He dubbed him “the most outstanding leader his country produced in the twentieth century.”

Palmer’s conclusion and Rabe’s analysis do not accord with a recent assessment on Jagan which, in fact, expose the still lingering influence of colonial and Cold War ideology prevailing in some academic circles. The eventual historical judgment on Jagan is already pointing to a conclusion closer to Palmer’s than that of the British Colonial Office, ‘local enablers’ of 1953 and the modern purveyors of that outmoded analysis driven by an ideological outlook which see Jagan as having contracted the ‘Marxist virus.’

Palmer was not as charitable to Burnham whom he described as “arrogant, self-assured, calculating, self-centred and overly ambitious.” He judged that Burnham’s “leadership or nothing” demand in 1953, and more particularly, his “neatly executed double cross” at the special congress called by him in 1955, “…. transformed the political culture of the country with devastating and enduring consequences for the body politic and social order.” Referring to Burnham’s and John Carter’s campaign to withhold funding to the two PPP governments, Palmer concluded that “both Burnham and Carter were willing to sacrifice their country’s economic development on the altar of political expediency…..His victory [in 1964] represented the triumph of Anglo-American machinations, tarnishing his claim to office and depriving him of moral legitimacy. ”

To demonstrate Peter D’Aguiar’s character Palmer related the claim D’Aguiar made while in the United States that the PPP had received money from communist organizations and his displaying two cheques which turned out to be forgeries with the bank on which they were drawn denying knowledge of them. He ridiculed his claim that thousands of Cubans were in Guyana.

The picture emerges of Janet Jagan as a one dimensional figure rather than the complex, multi- dimensional product of a conservative American Jewish home, a liberal and progressive activist in a racist, Cold War atmosphere, who gave up college to study nursing to help in the war effort and who translated that background into helping to initiate the struggle for independence in a small, deeply backward colony. Mrs. Jagan was clearly an equally committed partner of her husband, particularly in the Party which they founded.

Palmer quoted the British to the effect that Mrs. Jagan was a “brilliant organizer” but a “communist.” He avoids the trap of highlighting the racist and sexist accusation that Mrs. Jagan was the evil genius behind Cheddi Jagan, who introduced him to ‘communism’ and encouraged and guided him along that path, giving the impression that a ‘white’ woman was leading by the nose a ‘non-white’ colonial despite the latter’s undoubted intellectual capacity. He does not analyse her ideological posture, which though supportive of her husband’s, did not have the same intellectual depth or consuming passion.

Mrs. Jagan’s ideological underpinnings were highlighted in her work on social and economic issues of women and organising them from the late 1940s, her role as Editor of Thunder, the Party Organ in the critical early and middle years and in her abiding interest in culture. These do not receive Palmer’s attention. Had this analysis been attempted a more nuanced and balanced perspective on Mrs. Jagan’s role in organizing and publicity, while leaving policy and ideology to her husband, would have resulted.

Part 3

This third and final part of the review of Colin Palmer’s book, Cheddi Jagan and the Politics of Power, published in October by the University of North Carolina Press, begins with the decade of the sixties and the formation of the United Force. Its leader, Peter D’Aguiar, was not embraced by the British but the Americans gave him a sympathetic ear. The potent brew of D’Aguiar’s “zealotlike anticommunism,” “increasingly pungent racial divisions,” continuing economic challenges and the victory of the PPP at the 1961 elections, marked the beginning of the decade.The Government’s budget was designed to meet some of the economic challenges. Nicholas Kaldor, an internationally famous tax expert who had advised the governments of Turkey, India, Ceylon, Ghana and Mexico recommended new taxation measures. Palmer’s conclusion on the budget and the Minister of Finance confirms unbiased opinion even at that time: “Jacob’s budgetary initiatives were driven by the need to make the government solvent……..The minister’s analysis was characterized by considerable depth, a command of the country’s economic condition, and a series of sober measures for its development….. the policy measures he hoped to introduce aroused angry passions reflected the unthinking animus of the newspapers to initiatives associated with the PPP and the demagoguery and irresponsibility of the opposition leaders.”

The budget provided the occasion for the press and opposition to launch a campaign of distortion. Notwithstanding Jagan’s efforts to explain his budget proposals, to mobilize support for them and to compromise with the opposition, the latter was “busy fanning the flames of unrest,” incitement and street demonstrations which degenerated into ethnic violence and arson.

The Wynn Parry Commission of Inquiry which followed castigated both Burnham and D’Aguiar. Speaking about the opposition, the report said: “It was not long before these forces combined to form a veritable torrent of abuse, recrimination and vicious hostility directed against Dr. Jagan….” Palmer’s criticism’s of Jagan that he did nothing to heal the ethnic divisions and that they even served his purpose flies in the face of his acknowledgement of Jagan’s efforts to heal the racial divisions and hostilities by proposing a coalition government.

In fact, most of the criticisms of Jagan are adopted from opposition sources and repeated without analysis or are situated in the blanket condemnation of all politicians. Where any analysis justifying such statements take place, it is rather shallow. The introduction in 1963 of the Labour Relations Bill is deemed by Palmer to be a misjudgment because of the strike and violence it led to.

Palmer attributes the Bill to an immediate issue, namely, the desire of the PPP to gain recognition for the GIWU and to displace the MPCA which was a company union and did not have the support of the workers. Palmer missed an opportunity to explore another dimension surrounding the introduction of the Bill. The PPP was already aware that the British and American intelligence agencies were using the TUC and some trade union leaders, particularly Richard Ishmael, the head of the MPCA, to spearhead the attack against the government.

The PPP was also aware that its government had been brought to its knees the year before. The economy was also in a very weak state. Surely one possibility of deflecting its opponents, who were now openly supported by the Western powers, was to remove Richard Ishmael from a position of influence, weaken the Sugar Producers Association (SPA) and gain a foothold in the TUC, all in one fell swoop.

The introduction of the Labour Relations Bill could have been a calculated attempt by the PPP to place itself in a position of greater strength to defeat any further effort at destabilization. If there was a misjudgment, it was the failure of the PPP to learn its lesson from the year before when the opposition sacrificed all principles to remove it from office. Such sacrifice of principle continued when Burnham opposed the Bill which he had supported in 1953.

The PPP could not then have known that a decision had been taken at the level of President Kennedy and Prime Minister Macmillan to remove its government from office. Palmer set out of the consequences of the general strike of 1963: “As in February 1962, there were widespread acts of violence, arson, looting, and racially based attacks.” Guyana is yet to recover from the “most devastating eruption of racially inspired violence [which] erupted in April 1964.”

The fear, loss, pain and anguish of this period are captured by Palmer’s description of the violence and destruction of property during this period. Predictably, Palmer blames the “political leaders,” even though he understood quite well that the only way by which Jagan could get the Western powers and the opposition called off was if he resigned and give up.

After reviewing the involvement of the Western intelligence agencies in the involvement of Guyana’s problems between 1961 and 1964, Palmer concludes: “The compelling truth about British Guiana during those difficult years is that it was not free to choose its political path. Despite the vaunted invocations of democratic rights for all peoples, the imperatives of US and British national interests circumvented or prevented the actualization of such principles in Guiana.”

Palmer provides a synopsis of developments since 1964 and suggests that: “Guyana’s descent into economic chaos in the 1970s and the 1980s was a consequence of Burnham’s mismanagement, exacerbated by weaknesses in the global economy. But something else of more enduring significance was occurring. Guyana’s collective psyche was damaged by the assaults on its young institutions, the battering and circumscribing of dissent, the flight of some of the most productive citizens, and a worsening of the cancerous racial tumors.”

The premise for those of us who have always lived in Guyana and are engaged in its public affairs is the optimism that there a better future for those to follow. Palmer expresses that hope: “Contemporary Guyana shows the political, racial, and emotional scars of its troubles and unhappy past. But its future need not be burdened or circumscribed by them. The accumulated wrongs and missteps described in these pages will not be easily made right, but the tantalizing promise of societal reconciliation, peace and harmony among its people, a common national purpose, and economic development must remain alive with its leaders and citizenry.